But viruses don't have to cause disease - they can infect, replicate and exit without the host even realising it was there. Another view of viral infection is that we can exploit this very nature of viruses for our own means - meet: viral engineering (one flavour of biologically inspired nanotechnology).

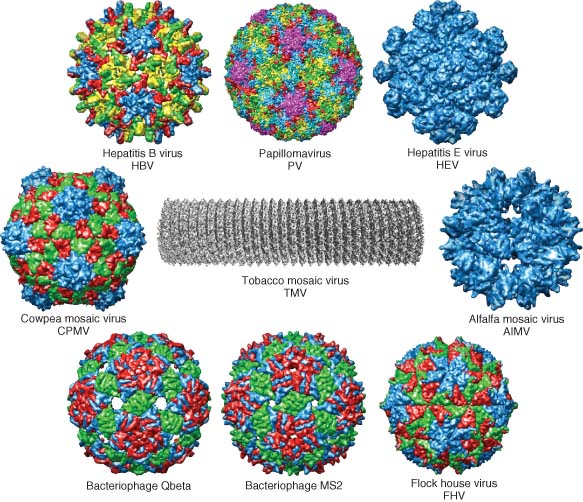

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="352" caption="Viral nanoparticles: the diversity"]

[/caption]

[/caption]Viruses are basically self-assembling storage containers that can enter and exit cells and deliver their contents, they are very small, are biodegradable, can be modified (relatively) easily and have an excellent ability to travel around the human body - one big bonus is that in some cases (plant viruses) they are also extremely cheap.

A recent review describes these 'viral-nanoparticles' (VNPs) as:

....dynamic, self-assembling systems that form highly symmetrical, polyvalent, and monodisperse structures. They are exceptionally robust, they can be produced in large quantities in short time, and they present programmable scaffolds. VNPs offer advantages over synthetic nanomaterials, primarily because they are biocompatible and biodegradable. VNPs derived from plant viruses and bacteriophages are particularly advantageous, because they are less likely to be pathogenic in humans and therefore less likely to induce undesirable side effects.

Of course there are many caveats with these applications such as we would have to thoroughly test the toxicity (including cell death and immunogenicity) of such VNPs as human pathogens may have been used as the basis of the design, although the use of plant viruses may circumvent these dangers. The pharmacokinetics, infectivity and replication of viruses will be assessed in animal models prior to use as so will the stability in both a physical and genetic sense. Yet there are plenty of uses for VNPs that would not have to be anywhere near a human patient.

Despite these difficulties, we have a great chance of developing improved VNPs through the application of genetic engineering and chemical modifications, allowing us to generate novel combinations of genes and properties into a single viral particle. We no longer have to rely on 'wild-type' virus genomes - we can improve on what is out there. By applying a better understanding of natural viral pathogenesis including cell entry, replication, gene expression, cellular tropism and immunomodulation we should be able to rationally design safer, more efficacious and cheaper VNPs for whatever purpose we want. We can now begin to think of viruses as a novel materal that can altered to generate improved properties and thinking this way should open up many possibilities for medicine, industry and science. This is a basic tenet of synthetic biology.

Synthetic biology meet virology.

As of today, this research has been moving at an extremely fast pace - viruses are now used in cancer treatments, bacteriophages have been used to kill off bacterial infections, viruses have been applied in materials science, improved electronics have been developed using viral particles and targeted viruses have been used in biomedical imaging technology. Yet as our understanding of virus/host interactions increases and research on the applications of these VNPs begins to move from in vitro to in vivo investigations we will see more and more uses for these novel materials in both the clinic and in industry. Look forward to the future of viral nanotechnology!

As the review finishes off:

The virus-chemistry interface remains an exciting place to be!

N.F. Steinmetz, Viral nanoparticles as platforms for next-generation therapeutics and imaging devices. Nanomedicine: NBM 2010;6:634-641, doi:10.1016/j.nano.2010.04.005

No comments:

Post a Comment

Markup Key:

- <b>bold</b> = bold

- <i>italic</i> = italic

- <a href="http://www.fieldofscience.com/">FoS</a> = FoS